Affordable housing challenge

Amid slowing demand and deteriorating profits, it seems now is a good time for housing developers — who are accused of being only interested in higher-end properties — to switch their focus to affordable housing, demand for which far outstrips supply.

Amid slowing demand and deteriorating profits, it seems now is a good time for housing developers — who are accused of being only interested in higher-end properties — to switch their focus to affordable housing, demand for which far outstrips supply.

But developers are saying that this would not be possible, especially if affordable houses are to be priced at the level the government and the people are seeking.

Deputy Finance Minister Datuk Othman Aziz, speaking at the 2017 Budget Focus Group Meeting on “Accelerating the Supply of Affordable Housing” last month, said houses priced up to RM165,060 are considered affordable to a median Malaysian household.

But developers said even a price of RM250,000 would not be a viable price tag, especially in the Klang Valley and other major urban areas. They argue that there are many aspects in the building cost that have continued to rise — most of which are the result of escalating land prices.

Real Estate & Housing Developers’ Association Malaysia (Rehda) president Datuk Seri FD Iskandar Mohamed Mansor noted that Khazanah Research Institute’s (KRI) report last year titled “Making Housing Affordable” concentrated primarily on three costs: material cost, machinery and equipment cost, and labour cost.

Of these three, he said, wages still show an increase. “In reality, the cost of labour has consistently been on the rise especially during times when there is a critical shortage of skilled labour,” he said in an emailed interview with The Edge Financial Daily.

“Many skilled workers trained in Malaysia have since returned to their country of origin or have moved to another country where the salary commanded is much higher than in Malaysia,” added FD Iskandar, who is also Glomac Bhd managing director and chief executive officer.

After paying for land to build a property project on, developers are required to surrender a portion for the construction of facilities, roads and drainage, social and community facilities, provision of open spaces, and utility companies, among others.

And, there is also capital contribution of “between 3% and 30% of gross development value to private utility companies such as Tenaga Nasional Bhd and Indah Water Konsortium Bhd, as well as other fees and deposits to various agencies and authorities”, said FD Iskandar.

Land prices have been going up and are higher in the city centre due to its scarcity. The premium for land conversion status, which is valued at a certain percentage of the tract’s current market value, will also increase. FD Iskandar said generally, the charge for land conversion has doubled within the past five years.

Land constitutes up to one-third of construction cost, which then makes cross-subsidising low-cost and affordable houses rather unsustainable for property developers, said the Rehda chief.

Even without factoring in the land price, he said low-cost housing selling price is capped at far below the cost to build it. And this results in the cost being pushed to other homebuyers.

“Currently, the cost to build low-cost housing — excluding land cost — is about RM105,000 for strata and RM75,000 for landed, whereas the selling price is controlled at RM42,000 maximum. Cross-subsidies for low-cost units are shouldered by buyers of other segment within a project, pushing prices up further,” FD Iskandar said.

In a prior interview with The Edge Financial Daily, KRI managing director Datuk Charon Wardini Mokhzani said: “Many of the issues of affordability in Malaysia are not so much the prices, but the incomes are not as high as they could be. Half of Malaysians earn less than RM1,600.

“It’s hard if you want to bring up a family — in Kuala Lumpur, especially. The possibility of you ever being able to buy a house is quite remote,” said Charon.

He also acknowledged that land prices are a major factor in raising property prices, but this is the result of a vicious cycle that needs to be stopped.

“Why have land prices gone up? I can sell it for a higher price than yesterday because people want the land to build houses. And why have house prices gone up? Because land prices have gone up,” Charon laughed.

Since KRI’s publication of Making Housing Affordable last October, the research institute has been saying property developers can achieve higher productivity and efficiency by switching to Industrialised Building Systems (IBS) method, where essentially a home’s components are prefabricated at a facility and later pieced together at the site.

“The first one or two projects may be more expensive than the old way because it takes time for people to learn how to do it. It takes time to get enough critical mass of suppliers,” said Charon.

Asked about this, FD Iskandar said the increase in employing IBS may be 5% to 20%. As such, “incentives must be given for IBS to work especially in the initial stages. For example, tax break for five years, 80% of government projects must be done through IBS, and others.”

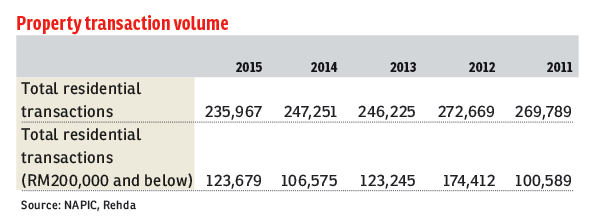

The Rehda president noted that homes that were sold at RM200,000 or below tended to have high take-up rates. Citing data from the National Property Information Centre, transactions of residential properties priced RM200,000 and below were above 100,000 units per annum between 2011 and 2015.

“[In 2015,] transactions of residential properties priced RM200,000 and below made up 52% of the total transaction, at 123,679 units,” he said.

Tan Sri Leong Hoy Kum, managing director of Mah Sing Group Bhd, which has been pushing for more affordable properties, however, thinks that properties “below RM1 million are still considered acquirable” by urbanites.

“However, we have to understand that different locations have different income level, resulting in different levels of affordability … on the fringes of the city, affordable properties are approximately RM500,000 to RM700,000; while properties priced below RM500,000 are located well outside the city,” he told The Edge Financial Daily.

Source: TheEdgeProperty.com.my

This “affordable housing” problem is actually a very simple problem, made complicated by stakeholders who refuse to admit their own shortcomings, preferring to blame others instead. The stakeholders range from developers, housing authorities, buyers as well as various agents in between.